Almost a decade ago now, the “War of Lebanon” came to a stop.

The reconstruction of the Beirut Central District began and stopped in 1983 when many believed, wrongly, that the war first ended. The story was to continue in the early 1990s.

As an architect graduating almost at the same time as Solidere, the real estate company charged with the reconstruction was created, I was very interested in the debate that shook the country, whether around the urban design itself, the politics behind it, or more importantly, around the validity of the forced redistribution of rights to the real estate.

In all cases, many things have happened since, Solidere has cleared the ruins, cleared whatever stood in its way of maximum return on investment, restored dozens of buildings, and finished the general infrastructure. Almost all the original opposition to the project was diluted with the fait accompli. And today, most architects are begging for work from the country’s largest private real estate holder, and few think of producing counterproposals anymore.

I personally believe that the form is lost, and any proposal for a radical PHYSICAL redesign of the central district of Beirut is futile. On the other hand, re-appropriation of the empty sterile streets through impromptu events and small scale interventions is still possible and is the only way to keep the heart of Beirut from transforming into nothing more than an elitist ghetto.

But that is not the theme of this presentation.

This presentation will address the issue of identity, national, cultural or otherwise, through the eerie parallel between the gradual destruction of the country’s physical form and the gradual abstraction of the National Currency’s design.

My argument is best illustrated by a series of pictures from Beirut and of designs of Lebanese bank notes.

[nggallery id=2]

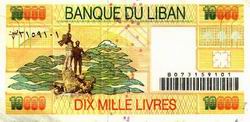

My contention is that there seems to be a very clear shift during the postwar period, from place-related banknote design, to a totally generic, abstract design, that is very similar to the gradual transformation of the physical landscape of the country into a mixture of unidentifiable architectures and of tabula rasas.

The question that remains unanswered is: is this a coincidence?

Social scientists will try to explain it by a need to “Start afresh”, zeitgeist believers will tell you that it is a normal representation of computer age art, while conspiracy theorists will swear it is all a premeditated scheme to rub all notions of identity and attachment to land from the mind of the Lebanese, and sell their soil to foreigners.

Whatever the case, it is, in my opinion, just like the design of the city centre, the reconstruction of the Beirut international airport, and of most of the country, another flagrant and unfortunate missed opportunity.

Money in Lebanon is perhaps the single most common denominator between the 18 or so communities that make up the Lebanese mosaic. The failure to recognise the importance of national currency as an archive of culture, is as dangerous as the systematic eradication of cultural heritage, as in the example of the Beirut Central District.

The hurried reconstruction (or re-destruction) of the BCD, was achieved under the slogan of a need for a neutral and unifying territory to mend post war scars.

An overzealous equation of “development” with “immediate reconstruction” has ultimately lead to the dilution of the identity of the place into a homogeneous, tasteful but flavorless whole. Today, the BCD is still a hole in Beirut. Clean. Pretty. But dumb.

While the rest of Beirut retains its character, the design of the bank notes has somehow been updated to reflect the basic flavors of the new centre: a regular grid, empty lots, and abstracted symbols, almost apologetically superposed, as on the new 10,000 Lira note. Even the color reflects that of the dirt filled lots.

This incredible reduction of Beirut to its Central District, is most eloquent in the new road that takes anyone from the brand new airport to the brand new centre and back in 7 minutes a trip. An itinerary that allows one to experience all of the future Beirut, but none of the present, insanely ugly and yet so charming Beirut.

The danger of this reduction is that of the transformation of a buzzy and diverse Mediterranean city, into a homogenous global business centre.

It is the transformation from heteropolis to monopolis, the reduction from national currency to one fit only for a game of monopoly.